Sunflowers (f)or Hitler: Where Vincent and Adolf weren’t so similar PART I

PART I: THE MYTH, THE MEN, THE PROBLEM

How much do we ever really know about people? With age we come more fully to understand the old notion that even with time we never fully know anyone, not our siblings, nor our spouses, our parents or even our children. If this is challenge enough, how can we begin to think we know the most famous names in history.

For many of us (in the West, at any rate), it was long before we had even completed elementary school that we knew the name Vincent Van Gogh and most likely had seen more than a few of his most famous paintings. At the same time, when it came to knowing anything about the worst and most hated people of the past the name Adolf Hitler is also learned at a young age.

But what prompted me to want to write a comparison piece between one of, if not the, most colossal monsters of the twentieth century and perhaps the greatest tragically misunderstood artistic genius of the late nineteenth century? It was reading a very long book by a very talented Norwegian author that got me ruminating first on Hitler, not the myth of the monster, but of the reality of the man. And in learning who that young man once was, I kept thinking of Vincent Van Gogh.

Vincent and Adolf aren’t often mentioned in the same sentence I don’t imagine, and yet I’ve come to believe they have more in common than one might at first glance realize. Like most villains and heroes of history they have long since been forgotten about as humans but rather are seen as mythical figures.

So what’s wrong with this? The trouble with myths, be they to venerate the great or vilify the unimaginably horrible is that they rob of us of the ability to see these people as they once were, as mere mortals, as men, as the poor, lonely outcasts of their worlds that these two were. But then what value is that? Why must we know who Van Gogh the man was; are his astonishing paintings not enough? More to the point, why delve into the human details of Adolf Hitler’s life — why even mar our personal time with such potential poison?

This whole line of thinking was inspired while I was reading The End, the final book of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-book memoir entitled My Struggle. I hesitated to even begin the now world-famous Norwegian writer’s memoirs when I learned that My Struggle in the original Norwegian is Min Kamp which in German is Mein Kampf. Get it, wink wink.

I did not get it. Being Jewish and not, I don’t think, nearly so hard-hearted as say a member of the Trump family, I naturally thought, wtf?!

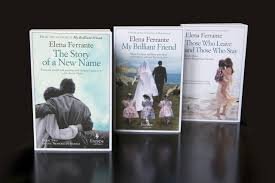

But then I read some reviews and it turns out Knausgaard is not a rampant anti-semite. This was not some Hitler apologist nor by any stretch of the imagination any kind of Holocaust denial. You need only read The End to know how very keenly aware Knausgaard is of the six million killed and all the horrible details that led up to those killings. It also helps that while white-supremacy and racism of all kinds seem to have been on the rise of late, they remain rather out of fashion in literary circles. There is in fact hardly any mention of Jews or Nazis, never mind Hitler, in the first five of Knausgaard’s books. Those are focused on Knausgaard as a father, as a writer, as a man falling in love, as the son of a very difficult father and more. They are, as labelled, memoir. They are also, to my taste, about as good as anything I’ve read in the 21st century, up there right alongside Elena Ferrante’s brilliant Neapolitan books.

It is only in the sixth and final of the My Struggle books, this one weighing literally more than double all the others, being well over 1,000 pages, that Kanusgaard goes on a kind of digression (except that it goes on for hundreds (plural!) of pages) about Adolf Hitler. Knausgaard, who spends most all those pages on Hitler in his youth - the Austrian/German man before he became the monster. And the Norwegian author makes the point that only by studying Hitler in his formative years can we understand anything about the nature of evil. And let me be clear, he thinks Hitler the great monster we all do; he’s just read a whole hell of a lot more about it than even the most avid History Channel fan (Tony Soprano I’m looking at you).

If we exclusively view the future German dictator who created and enacted the Final Solution in which he came perilously close to wiping out the entire Jewish race as evil incarnate then we simplify and misunderstand evil in the first place. Knausgaard understands his reader (his reader who is now six books and nearly 3,600 pages deep into a very literary memoir) and that in his efforts to even try to present the objective facts of Hitler’s youth is bound to upset people. And yet, Knausgaard points out how some (rather famous) biographers of Hitler (one in particular whose name I’ve forgotten) have gone the tempting route of painting each and every moment of Hitler’s life as representative of and proof of his monstrosity. But Knausgaard claims, and I wholeheartedly agree with him, that this is not only inaccurate and simply not true, but it also misses the point entirely – it also, I think, is the kind of thinking that dooms us to repeat history.

There is for instance no real evidence, owing to Knausgaard’s extensive research, that Hitler was much of an anti-Semite before he moved to Vienna. He even had Jewish acquaintances (Hitler had very few friends his whole life). There are in fact so very many factors involved in the devolution that took this man from man to abhorrent bastard. What Knausgaard does in painstaking and yet ever riveting detail is present so many of the facets of Hitler’s youth that slowly, slowly built him up to become the dictator he did. How none of it would have been possible if not for a very lost young man finding meaning in his life by fighting for the Germans as a decorated soldier in World War I. Think of marching Nazis and those grand parades and you get an idea of where Hitler got all those ideas from. None of what was to come would have been possible if not for the kind of mother he had and how he lost her early, about the extremely strict father he did not get along with (I’m sure we all guessed that detail)… but then also being a total failure of an artist (turns out he did not once but twice tried and failed to be accepted into the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna). Knausgaard, probably previously best known as a novelist does an extraordinary amount of research for this book. He reads Mein Kampf of course as well as the memoirs of those who knew Hitler in his youth not to mention a swath of Hitler biographies that stacked up are likely as tall as myself and then some. And what I learned that I had not known before was not that Hitler was a talentless hack when it came to painting but rather that he was just lazy with it. Despite serious delusions of grandeur, a characteristic as defining of Hitler’s personality as his taciturn and extremely anti-social nature, in those years in Vienna, Hitler slept late, dreamt often about a girl he never spoke to, was unemployed and did not engage in nearly enough painting to become who he so clearly thought he deserved to be.

Still, hard to view that heinous excuse for a human as anything but a flaming ball of hate.

Which brings us to Van Gogh (ah, relief), who in terms of myth vs actual person, challenges us in very different ways. For just as we want to take every moment in Hitler’s life and want to spit on them, we tend to go the other way with dear Vincent, so beloved is the myth of the man, thanks to the tragedy of his life and the stunning beauty of his art works that he left for a world that may not have deserved them. Take the Don McLean song, “Vincent”, the one that starts “Starry, starry night”:

For they could not love you

But still your love was true

And when no hope was left in sight

On that starry, starry night

You took your life, as lovers often do

But I could have told you, Vincent

This world was never meant for one

As beautiful as you

It was Anthony Lane’s New Yorker essay “Why Do Filmmakers Love Van Gogh” that illuminated the point for me:

Van Gogh sold one painting in his life, but we—so we reassure ourselves—would have purchased everything, down to the meanest daub. We would have summoned medication and therapeutic care for his afflicted brain. The fatal bullet could have been extracted. We could have saved him.

This is nonsense. Although we know more, we are no better. Most of us would have avoided van Gogh, ignored him, or taken offense at him, as his contemporaries did. As for fame, he likened it to “sticking your cigar in your mouth by the lighted end.” He was a difficult soul, and some of his sexual dealings were edged with threat. “I always have an animal’s coarse appetites,” he confessed to Gauguin, and one of the witnesses cited in the Arles petition claimed that van Gogh was “given to touching the women of the neighbourhood, whom he follows right into their homes.”

As mythic figures Hitler and Van Gogh could not be more different. The one a seething, slobbering, moustachioed manifestation of demonic evil. The other a sorely misunderstood man too sensitive, beautiful and brilliant for an average peasant person to understand.

And yet to read a little of their actual histories, to learn some of the truth we notice these two had quite a lot in common.

To be continued …